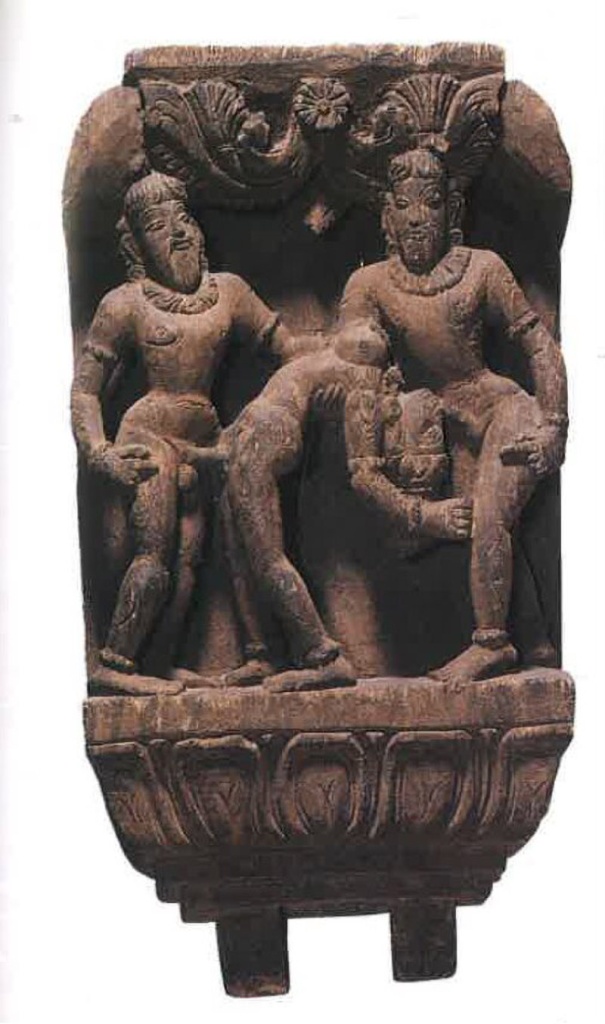

In the Naomi Wilzig Collection, there are many different references to the Kamasutra: statuettes and figures described as being in “Kamasutra positions,” bracelets with images on the circumference with “Kamasutra scenes,” and temple pieces and sculptures with carved images of figures described as representing Kamasutra. See, for example, this Indian sculpture (Image 1) carved from a tree trunk, which is said to be from around 1850 from either the Khajuraho or the Konarek temples, which shows numerous nude figures engaged in various sexual acts and positions and which is described as “illustrating ‘Kama Sutra’ poses”[i].

During my internship in the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection project at the Research Center for the Cultural History of Sexuality at Humboldt University in Berlin, I became interested in understanding what the Kamasutra actually is. What makes a sexual position a Kamasutra position? Is it even culturally and historically correct to make such a distinction?

In this blog post, I will describe the history of the Kamasutra, its reception in the West, and its unduly reduction of the Kamasutra as a sex handbook. For this, I will first give an overview of the translations of the Kamasutra into English and then focus on the marketing of the Khajuraho temple site as a “Kamasutra” destination.

What is the Kamasutra?

I do not have a distinct memory of when or how I got to know about Kamasutra. I just associated it with being “something about sexual positions.” Most likely, this view was influenced by countless Western mainstream media’s portrayal of how Kamasutra can be used to enhance your sex life. Most modern translations and versions reinscribe an exoticized view of the Kamasutra and market it as a self-help guide to better sex [ii].

Contrary to mainstream Western portrayal, the Kamasutra is not only a guide for sexual positions but also a text on how to live a pleasurable and desirable life in general. Kamasutra is a Sanskrit word composed of the word kama, which translates into desire, and the word sutra, which translates into thread. In the original Kamasutra, desire is defined as any kind of desire that can pleasure all your senses. It is estimated that the Kamasutra was written between the second and fourth century AD. Most often the Kamasutra is ascribed to the Indian philosopher Vatsyayana, however some believe that the text was compiled by several different texts, which could have had several authors [iii]. This version of the Kamasutra was written in Sanskrit, and at present there exist several translated versions and interpretations of it.

The Sanskrit version, which is often attributed to Vatsyayana, has seven different parts, all dealing with ‘how to lead a pleasurable life’ from different aspects. The first part is on general practices, the second describes in detail various positions for sexual intercourse? between heterosexual partners. The third part describes how a man can obtain a bride. The fourth is a text on which duties the wife has. The fifth part describes how you can have a relationship with other men’s wives. The sixth part is a text describing relationships with courtesans, and the seventh part is a text on the “secret formulae designed to ensure success in sexual activities”[iv]. A big part of the texts relates to the importance of using various art forms (dancing, singing, writing, painting, etc.) to obtain different kinds of pleasures and desires. So, while there are many more aspects in the Kamasutra than mere suggestions for sexual positions, it is the second part on sexual positions that have become synonymous with Kamasutra. This reductive reception has a lot to do with the colonial history of India.

Translating the Kamasutra

The English orientalist Richard Burton is often credited for “discovering the Kamasutra” [v]. He was a diplomat for the British Colonial Empire and often referred to as a “traveler” or “explorer”, and was very interested in the erotica and sexual aspects of the countries he traveled through; Burton was part of the Kama Shastra Society, which published the first English translation of the Kamasutra in 1883 (at this time India was still occupied by the British colonial empire). Scholars are not entirely clear on who the members of The Kama Shastra Society were, but it seems to have consisted of a small group of English men. The aim of the Kama Shastra Society was to publish “erotica from the East for the sexual liberation of Victorian society” [vi].

The 1883 English translation was titled The Kamasutra of Vatsyayana and has been heavily criticized by several scholars for being poorly translated, neglecting crucial parts, and being a simplified and exoticized version of the original text. Among the several things that were left out were accounts of male and female same-sex sexuality (Only in the context when a man is not able to satisfy his multiple wives, female same-sex interactions were translated and included). Burton was, in general, very occupied with the idea of sexually liberating the female citizens of Victorian England (which was also the aim of the Kama Shastra Society), and this highly shaped the translation of the Kamasutra. Scholars such as Kumkum Roy and Jyoti Puri have, by comparing different translated versions of the Kamasutra through a feminist lens, highlighted how Burton’s translation both acknowledged women’s sexual pleasure but, at the same time, framed it as something that needs to be normatively managed and regulated [vii].

According to Roy, Richard Burton’s translated version was “probably the first version to describe the Kamasutra as a ‘work on love’”[viii], and despite the heavy critique of Burton’s translation, this version still influences most mainstream published work on the Kamasutra. The reception of the Kamasutra exemplifies that translating written pieces of work is not a neutral process, especially in a colonial setting. The Kamasutra is still entangled in a narrative of being a text for sexual liberation, which also shows in works done by Indian scholars.

A Hindi version of the Kamasutra, first published in 1911, which is often used by scholars today, has been criticized for promoting homophobic sex education, which focuses more on the absence of sex than sex. The interesting thing about this version and the critique of it is that the author, Pandit Madhavacharya, in his claim to translate the Kamasutra from an Indian nationalist perspective, ends up reinforcing a Western and simplistic view of the Kamasutra [ix].

Another example of a scholarly recognized translation is S.C. Upadhyaya’s Kamasutra of Vatsyayana: Complete Translation from the Original, which was published in 1961, has likewise received critique for underpinning the colonial legacies of the readings of the Kamasutra, despite the effort to distance itself from this problematic reading of it. While in a US context, the Kamasutra is often portrayed through mainstream, popular culture as “the sex handbook”, in India, to a larger extent, the Kamasutra is scholarly studied and debated. Puri is critical of both, arguing that: “[…]both accounts reproduce questionable narratives of ancient India to promise sexual liberation from degrees of extant sexual repression; put differently, narratives of a liberal Indian/Eastern past and repressive present support the discourse sexual repression, with “the Kamasutra” as the mediating factor in these cases”[x].

Exoticizing of the Kajuraho Temple Site

Another example of the exoticizing of the Kamasutra is the Khajuraho temple site, located in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India. Originally, the temple site consisted of eighty different temples, but today, the temples of Khajuraho are a complex of twenty-two temples that have been listed as a UNESCO heritage site since 1986. The Khajuraho temples are estimated to have been built between 950 and 1160 AD by the then-ruling Chandela dynasty. The purpose for building these temples is still unknown, but there are several myths connected to the existence of them. According to one myth, the temples were constructed to visualize the loving relationship between the Moon god and an earthly woman. Some scholars argue that the temples and the Kamasutra sculptures (Image 2) were built to promote tantric sexual practices (the sources I have on this all talk about the temple site as one collective entity, although they are actually different), others argue that while the sculptures might be visual representations of tantric practices, the aim was instead to decrease sexual desire. Others, again, argue that the temples were built as visual representations of the Hindu gods Shiva and Parvathi [xi].

TS Burt, a British officer working for the company Royal Bengal Engineers, is often credited for “re-discovering” the site in 1838 [xiii]. Through Burt’s notes, it is evident that at least one of the temples was still used for worship by the local community at the time. Some decades later, the Khajuraho temples were documented by another British officer, who described some of the sculptures as “highly indecent and disgustingly obscene”[xiv]. It is unclear whether the sculptures at this time were thought of as Kamasutra sculptures, but the narrative of these temples as ‘something highly sexual’ persisted.

After India’s independence in 1947, the then-prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, initiated a promotion of the Khajuraho temples with the aim of attracting Western tourists to the site. Since then, the tourist promotion of the temples has continued, and today it is possible to fly directly to the small city of Khajuraho from the capital city of Delhi. The Khajuraho temples are now heavily promoted as “Kamasutra temples” and have become a tourist site marketed to Indian and foreign tourists as a place of eroticism and “sexual liberation”. In 2015 alone, around one million people visited the temples in a town with a population of around 25.000[xv]. This is despite the fact that only about 10 % of the sculptures at the Khajuraho temples include explicit erotic representations. Other sculptures include, for example, visualization of teachers, students, dancers, and musicians.[xvi]

This marketing of the Khajuraho temples as a site for Kamasutra is another example of how the reductive view on the Kamasutra influences not only western mainstream media but also parts of the tourism industry in India.

Ending Reflections – How to Describe and Display Kamasutra Objects in Museums?

“Promoted as a superior sex handbook, the Kamasutra promises pleasure and substance for inspiration. In effect, an unreflective account of the Kamasutra reinscribes oppositions between the ancient East and the contemporary West, between contortionists and inspired couples, but also serves as a link between orientalist fantasy and female and male sexuality in the United States. To wit, the politics of historical, unequal relationships based on discursively constructed differences are elided”[xvii].

Even though the original Kamasutra had detailed descriptions of positions for heterosexual intercourse, I am still not sure whether to use “Kamasutra” to describe sexual positions – in museums or elsewhere. Because the Western notions of what Kamasutra means are so entangled with orientalist narratives of the “exotic East”, I would argue that it is necessary to properly contextualize the Kamasutra instead of focusing on the sexual positions itself. This could, for example, entail the display of Kamasutra-related art objects in an exhibition focusing on erotic orientalism and highlighting the implications of that, and/or not focusing solely on the erotic aspects but placing the Kamasutra objects in a larger cultural context. For this, I believe a constant focus on collaboration with people and the use of sources that represent a different perspective than the white Western narrative is necessary.

[i] Naomi Wilzig, Forbidden Art – The World of Erotica (Schiffer Publishing Ltd, 1998), 93. [ii] See for example, Kama Sutra: The Book of Sex Positions or Kama Sutra, or The Ultimate Guide to The Ancient Art of Sexual Pleasure. [iii] According to Kumkum Roy, this is a very common feature of Sanskrit texts written in that period. Kumkum Roy, “Unravelling the Kamasutra,” Indian Journal of Gender Studies, (1 September 1996): 155. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/097152159600300202. [iv] Jyoti Puri, “Concerning Kamasutras: Challenging Narratives of History and Sexuality,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 27, no. 3 (2002): 157. [v] Ibid., 603-639. [vi] Besides the English translation of the Kamasutra, the Kama Shastra Society also published English translations of Ananga Ranga in 1885 and the Perfumed Garden of Sheikh Nefzaoui in 1886. For more on this, see Puri “Concerning Kamasutras,” 611. [vii] Ibid., 618. [viii] Roy, “Unravelling the Kamasutra,” 165. [ix] For more on this, see Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai, Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History (Palgrave: London, 2000), 236-240. [x] Puri “Concerning Kamasutras”, 606. [xi] The differences between tantric practice and Kamasutra sexual practices are not always clear in the texts. [xii] “Wood carving, temple mount, probably removed from a temple at Khajuraho, three deity type figures, Indian 18th Century, 17″ tall”. From: Naomi Wilzig, Forbidden Art, 77. [xiii] For a critique of the colonial narrative of “discovery” see: Swetha Vijayakumar, “The Sacred and the Sensual Experiencing Erotica in Temples of Khajuraho,” Open Edition Journals (December 2017), DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/viatourism.1792 and Puri, “Concerning Kamasutras”. [xiv] Vijayakumar, “The Sacred and the Sensual”. [xv] Ibid. [xvi] The renewed interest in the temples and the erotic sculptures also led to a continued looting of the temples. It is estimated that between 1965 and 1970 more than 100 (erotic) sculptures valued at several million dollars were stolen and smuggled abroad. This could lead one to argue that objects from such temples should be returned to its original place. While that is also an important reflection, it is out of the scope of this blog post to deal with such a discussion. See Hamendar Bhisham Pal, The Plunder of Art, (Abhinav Pubns, 1992): 30. [xvii] Puri, “Concerning Kamasutras,” 605.

Joan Ellingsgaard Kindberg holds a B.A. in Modern India and South Asian Studies (University of Copenhagen) and an MSc in Development and International Relations, Global Refugee Studies (Aalborg University, Copenhagen).