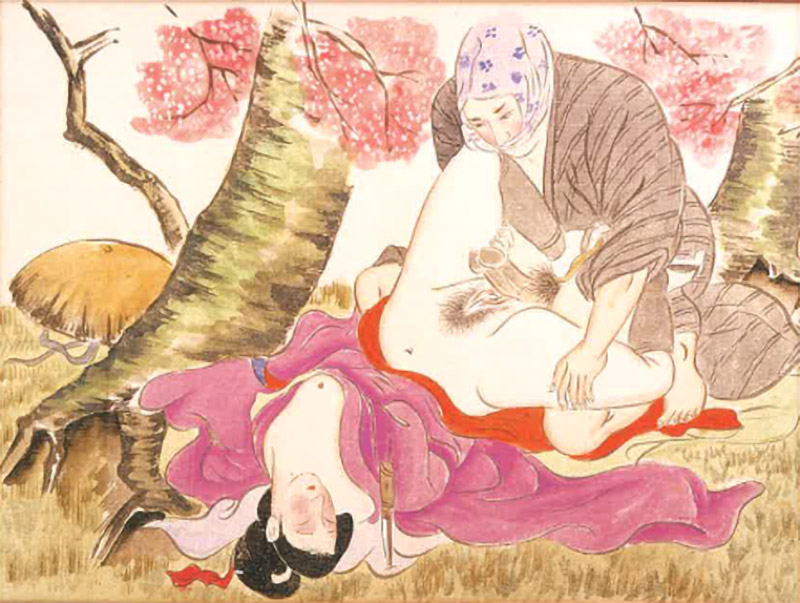

The Naomi Wilzig Collection, exhibited at the Wilzig Erotic Art Museum (WEAM), features several “shunga,” a type of erotic print from Japan that differs in many ways from Western representations of sexuality and has often sparked a great deal of interest among Western audiences.

Shungas were produced in the 15th century and were inspired by Chinese pillow books. The word means “Spring pictures,” but they were also commonly called “laughter pictures,” which demonstrates a rather light approach to sexuality and erotic art. Naomi Wilzig collected dozens of these artworks between 1983 and 2005.

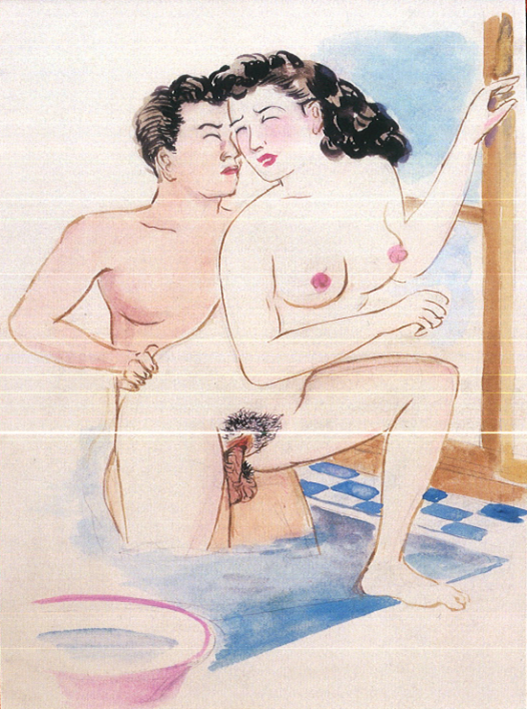

It shows a half-naked couple engaged in penetrative vaginal sex on the floor. Behind the couple, there is a low table with upturned cups. It is a spontaneous scene of two people caught up in the moment, their cheeks red from the effort and perhaps from alcohol. Their layered clothing is in their way, making them appear to struggle to access the other’s body. The intention is to show an everyday scene. However, the proportions of the individuals are partially exaggerated; the penis and the vulva are larger than life. These images differ from their precise and realistic Chinese counterparts, which are meant as practical guides, demonstrating which sex positions are most beneficial for health. The positions in shunga are exaggerated, comical, disproportionate, and often anatomically impractical.

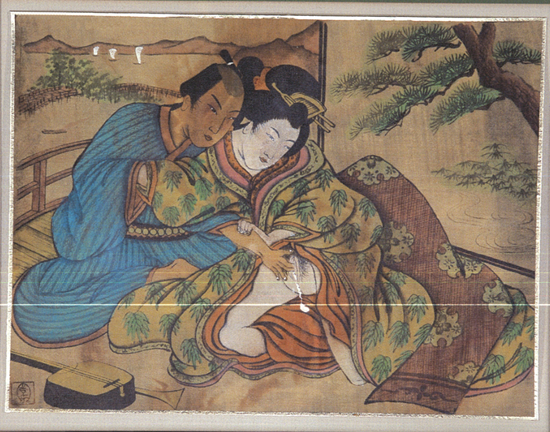

This image is from the “golden age” of shunga and was most likely printed with the woodblock technique. It is in the ukiyo-e style, meaning “the floating world.” The floating world refers to a certain aspect of Japanese life between the 17th and 19th centuries, very aware of the ephemerality and impermanence of the existence of life and derived from a Buddhist concept. For this type of shunga, the depiction of mutual consensual pleasure for both the man and the woman is important.

Sexual fluids are regularly depicted in shunga, signaling orgasm and its desirability. Shungas are deeply erotic, but as eroticism is not universal, the eroticism of shunga shows what Japanese people in the 17th through 19th centuries found erotic, including perhaps richly patterned kimonos, a certain curve of the neck, exaggerated genitals, and mutual sexual enjoyment. Additionally, although not as common as heterosexual scenes, some shunga showed two women or two men together. A common figure in the golden age of shungas are wakashū, an Edo period “third gender” composed of young adolescent boys who were dressed like women and were highly sexualized by both genders.

While Western erotic images were mostly made by men for the enjoyment of men and often only accessible to a select few, shunga were not taboo or hidden. They were enjoyed by both men and women, alone or with others, in public and in private. These Japanese images of sexuality would even be incorporated into a wife’s dowry. To the surprise of many Western observers, shunga was also believed to have some apotropaic properties, like protection from evil spirits and misfortune. Some records tell of warriors going to battle with erotic prints on their armor — what a sight it must have been!

It was not taboo to make shunga, and most of the great painters and artists of the time produced shunga. Hokusai, for example, the artist of the “Great Wave of Kanagawa,” also produced erotic paintings. Shunga sold well, and depending on the quality of their manufacture, their selling price could reach significant sums, especially if they were commissioned by a great lord. They were often embedded into scrolls or leaflets, printed in several hundred copies, and sold in bookstores or borrowed from itinerant tradespeople. The use of woodblock printing allowed mass production and reduced the cost. A commoner could buy shunga prints for the price of a meal, while great lords could still ask painters for individual scrolls painted with high-quality materials, gold, and ground seashells. The diversity of shunga’s audience perhaps also explains the diversity of the social classes represented, since most social classes, especially prostitutes from the “pleasure district,” had their place in shunga. Shunga began to fade during the 19th century and would almost completely disappear with the Westernization brought about by the opening of Japan in 1854.

In view in the Yiddish Book Center’s Brechner Gallery now through March 2019, Lost Synagogues of Europe is a collection of early twentieth-century postcards on Jewish themes, many of them depicting synagogues in Eastern Europe that were destroyed during World War II. The postcards come from the collection of Frantisek Banyai, a Prague-based entrepreneur and son of Holocaust survivors who began amassing the collection 40 years ago and continues his search today

Finally, a dive into the building blocks that help a site work particularly effectively. Hopefully, you’ll finish the post with a fresh perspective on your own site: you’ll be able to identify how to make work better for your visitors and advocate for effective change as part of the organization’s strategy. Of course, we threw some sites we built at Cogapp into the mix, too.

Western influences

This taboo surrounding shunga in Japan, which continues until today, can be explained by a multitude of reasons, but it is impossible to ignore the responsibility of the Western powers in the 19th century. The growing influence of Western powers generated one of the fastest modernizations in history after the end of Japanese isolation in 1854. Over the course of half a century, the country passed from a pre-modern feudal society to a world superpower capable of defeating China and Russia.

To be recognized by the West, it was necessary to acquire Western technologies but also to reduce the cultural distance and adopt a degree of Western values. The slogan “Enrich the country, strengthen the army” was accompanied by “Leave Asia, Join Europe.” The things that most clashed with Western values were banned or reformed, including shunga, which shocked and fascinated Westerners. The Meiji government soon realized that the circulation of erotic images contributed to a Western perception of Japan as a “primitive” or “shameless” nation. A series of laws prohibiting shunga were passed between 1868 and the beginning of the 20th century. Shunga circulated with more and more difficulty, often functioning as novelty items for the Western market.

The adoption of Western values and elements of Western culture, in addition to the increasingly Western audience of shunga, can be seen in this painting from the Naomi Wilzig Collection, which was produced as a souvenir picture for US soldiers after World War II.

Along with this cultural shift came the evolution of a style that showed an increase in violent or non-consensual sex scenes that catered to a male gaze.

This shift towards the male gaze was accompanied by an increased heteronormativity since wakashū was completely absent from shunga produced in the late 19th century.

Collecting Shunga

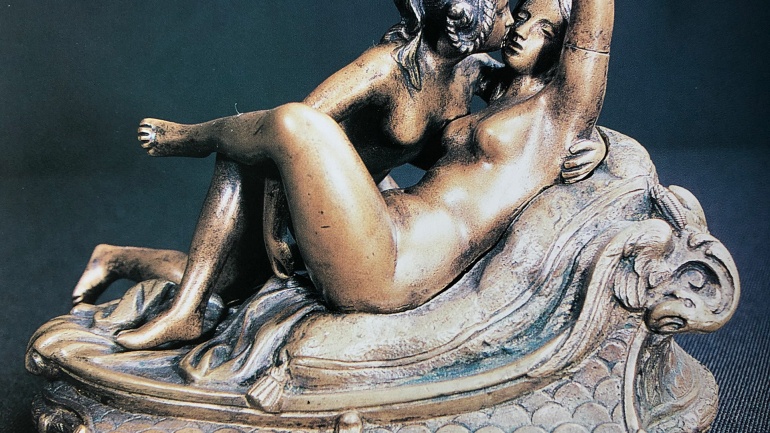

Successive waves of interest in Japanese art hit Europe and North America since the opening of the country. Ceramics, lacquered boxes, or prints were the pieces of choice, but imports also included shunga and small statuettes called netsuke, whose connotation can be sexual. Japanese erotic objects immediately fascinated the West and have been central to Japanese-Western relations since the 19th century. Commodore Perry, the American military leader who forced the opening of Japan, was offered shunga when he departed. Shunga has been found in the homes of Emile Zola, Picasso, Rodin, and George de Witt and in secret rooms of the British Museum and the Louvre. Interest in shunga is still vivid in the West, as exemplified by several recent exhibitions of Japanese erotic art, most notably at the British Museum in 2013, and by their extensive inclusion in the WEAM collection.

Shunga are works of art in their own right and very representative of the society from which they stem. In their golden age, they were objects reflective of Edo period Japanese society, displaying a sexuality that was more lighthearted, mutually pleasurable, and egalitarian. They immediately fascinated the West, in part because they were so different from the erotic objects Westerners were accustomed to, but in part due to their new Western audience, the popularity and authenticity of shunga declined alongside Japan’s accelerated modernization. Today, these are still controversial images, both in Japan and in Europe, but they also seem to be increasingly appreciated, collected, and displayed.

For more on shunga, see: Timothy Clark, C. Andrew Gerstle, Aki Ishigami, Akiko Yano: “Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art” British Museum Press, 2013.

Thomas Pauvret has a BA in history and is currently completing his MA in heritage and development in the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Program TEMA+. From March to May 2021, he completed an internship at the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection project at Humboldt University, Berlin.