As an intern at the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection Project at the Research Center for the Cultural History of Sexuality at Humboldt University, my job has been to work on the documentation and to write new descriptions for the objects represented in the catalog Erotic Treasures. The ultimate goal of this project is to create an online database containing the entire Naomi Wilzig collection, complete with new descriptions, titles, and searchable subject terms. This blog post lays out some of my thoughts about cataloging in general and Erotic Treasures in particular, including its organizational structure and the benefits and losses of doing away with this structure, issues I encountered with terminology and the practice of labeling, and the various ways I have tried to meet these challenges.

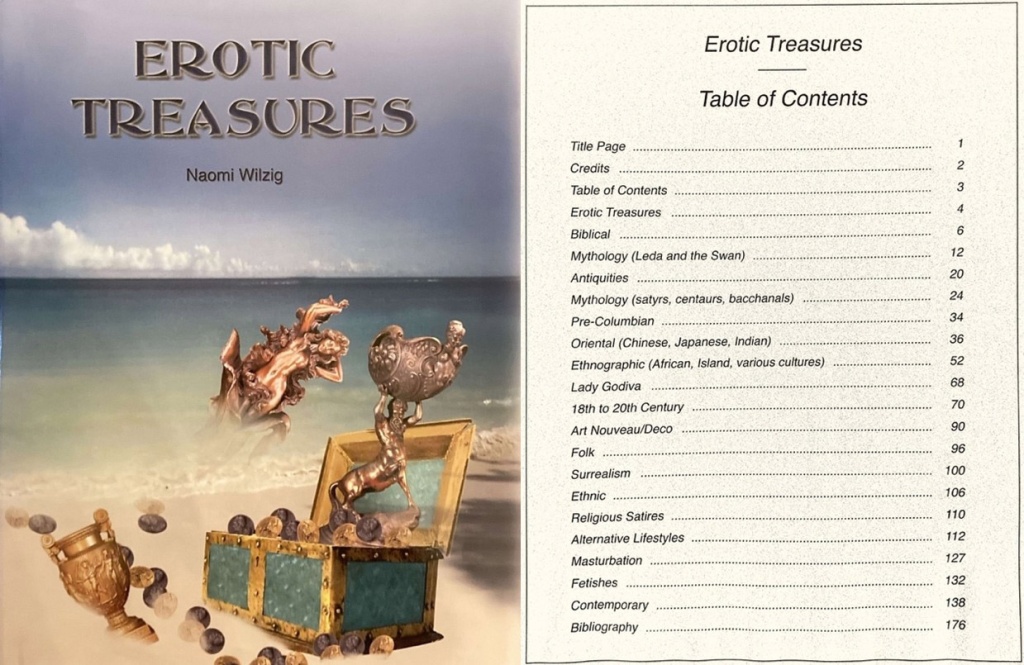

Erotic Treasures was published by Naomi Wilzig in 2005 and contains just over 300 objects from the World Erotic Art Museum, which houses Naomi Wilzig’s personal collection of erotic art. The objects are arranged into categories rather than strictly chronologically. Within each category, objects are presented individually with very brief descriptions and only basic information. There are no long contextual or interpretive texts (see images 3 and 5 for examples of the catalog’s format).

The organizational structure of Erotic Treasures carries meaning and especially conveys a narrative of “progress.” We start with the origins, with Adam and Eve and the Ancient Greeks and Romans, represented in the collection by a mixture of genuine artifacts and modern objects, often kitsch, utilizing Greek and Roman mythological imagery. Then we go to the pre-modern, which includes the non-Western: “Pre-Columbian,” “Oriental,” and “Ethnographic.” Lady Godiva brings us back to the West and, in this progress narrative, ushers in modernity. In the final categories, from “Ethnic” to “Fetishes,” we reach the “others” within modern Western society. Together with the objects in “Contemporary,” these final categories complete the evolution of human sexuality, indicating the diversity and tolerance of modern, Western sexuality and sexual practices. In short, the catalog walks us through a narrative that begins in Western myth and ends in the Western modernity, treating the non-West and the pre-modern as “stepping stones”, and utilizing modern sexual diversity as a justification for defining the contemporary West as the pinnacle of sexual progress (see image 2). This problematic teleology of Erotic Treasures is reflective of a similar problem in the former permanent exhibition of WEAM, as pointed out by Katherine Sender in her article “Selling Cosmopolitanism: Same-Sex Materials in Museums in Asia, Europe and the United States”.[i]

The new online database in which the Naomi Wilzig art collection will be presented is non-linear, so the objects will no longer be grouped into these categories or arranged in this order. The narrative of Erotic Treasures, which places the non-West in the perpetual pre-modern and modern, liberal, Western sexuality as the apex of human sexual development, will be lost. In its new form, any information that used to be conveyed by the placement of the objects in the printed catalog needs to be either explained outright in text or will be lost. The idea that world history has culminated in Western sexual liberation can, uncontroversial, I think, be done away with. However, other elements of the catalog’s categorization are more complicated.

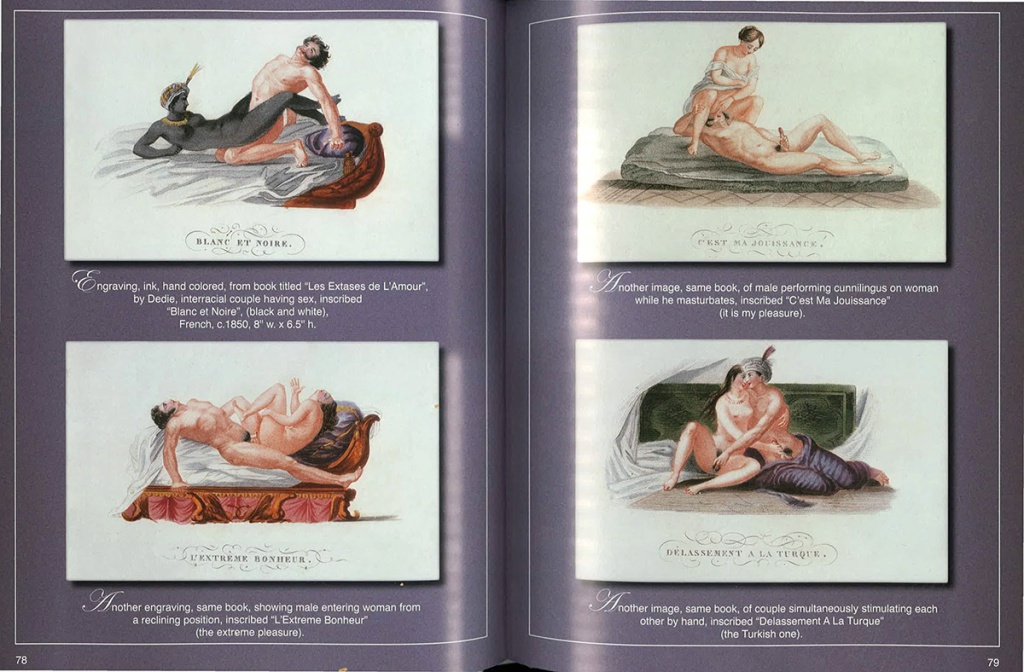

One complication stems from the fact that the collection skews heterosexual and white. For example, Erotic Treasures shows 21 objects containing depictions of Leda and the Swan, 11 of Adam and Eve, and countless other white heterosexual couples. In an unordered mass, it would be hard to find the relatively few items depicting BIPOC or LGBTQI+ people. To be found, items like these need to be labeled, or else risk erasure. But by labeling, we risk ghettoization and essentialization, reducing objects down to their perceived “otherness” and segregating them from the objects and bodies we normalize. If seven of the Adams and Eves are white, three ambiguous, and one Black (as is the case in Erotic Treasures), then how do we ensure that this one depiction doesn’t get lost in a sea of whiteness without also reifying the idea that to be Black is to be the “other” and to be white is the default or norm? Image 3 exemplifies both how items in the collection and the language used to describe the few objects that depict something other than white heterosexuality can be othering or ghettoizing.

Beyond the question of whether to label is the equally important question of how to label. In Erotic Treasures, the language around sex was often veiled––couples are “entwined,” and men are “tumescent.” Is the subject term of “homosexuality” too medicalized and “rimming” too informal? Why are there no thesauri or established cataloging terms for sex positions––should we just make up our own? The terms that exist for sexual practices are often oddly euphemistic, incredibly loaded, or explicitly racist, colonialist, sexist, cis/heteronormative. For sex positions alone, “spooning” feels euphemistic, “scissoring” is loaded and problematic, “missionary position” is racist and colonialist, “girl-on-top” is heteronormative, etc. Resources like Homosaurus, the Planned Parenthood Glossary, and the internal thesaurus of the Kinsey Institute were helpful, but we often found ourselves lacking the language to describe what we were seeing and even complicit in various forms of linguistic violence.

Even now that the internship is ending, I don’t have answers to most of these questions. One ameliorative practice that I have found helpful in approaching this project is emphasizing the subjectivity and particularity of the collection and, in doing so, resisting its claims of universality. The collection sometimes seems as though it is meant to show the eroticism of the world and the differences and similarities of human sexuality across all time and space. It’s this claim to universalism that causes many of the collection’s problems. If we think of it less as a collection of “World Erotic Art” and more as the Naomi Wilzig collection, then the collection has fewer pretensions of speaking for all people and can be viewed as rather speaking for one person whose tastes, quirks, and personal sense of eroticism are its guiding principle. Far from depicting the world’s sexuality, this collection very thoroughly depicts the artistic and erotic tastes of its collector, who, with no background in erotica and with a serious rebellious streak, amassed one of the largest collections of erotic objects in the world. Perhaps the most obvious example of the collection’s particularity is its disproportionate emphasis on Leda and the Swan, which is by far the most common subject in Erotic Treasures. Naomi Wilzig was a fan of Leda and the Swan and even commissioned a portrait of herself as Leda (see images 4 and 5).

To the museum’s credit, the name was changed from World Erotic Art Museum to Wilzig Erotic Art Museum in 2019 to more accurately reflect the galleries as the personal collection of its founder rather than a universal representation of erotic art from around the globe.

Naomi Wilzig had no background in art history or museum curation. She opened the museum as a way to share her passion for collecting erotic art and, in creating the galleries, possibly emulated the practices of other museums at the time, attempting to create a narrative from her highly idiosyncratic collection. However, there is evidence that she was open to listening to others regarding how her collection could be displayed. In her article “Perverting the Museum: The Politics and Performance of Sexual Artefacts,” Jennifer Tyburczy shares an anecdote about how, once Tyburczy told Naomi Wilzig that she finds the cloistering of the section on homosexuality behind a black curtain to be problematic, Wilzig stood up immediately and tore down the curtain.[ii] I think the primary ameliorative practice that I was able to successfully develop in this internship is the tearing down of a curtain: the removal of the objects from the categories and narratives in which published catalogs confined them. As far as how to build up a new database, one which balances ghettoization with erasure and is able to describe precisely without leaning on language that can alienate and dehumanize, we were able to take some steps in the right direction, but we still have a long way to go.

[i] Katherine Sender, “Selling Cosmopolitanism: Same Sex Materials in Museums in Asia, Europe and the United States,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, (2020) 26 (1): 35–61.

[ii] Jennifer Tyburczy, “Perverting the Museum: The Politics and Performance of Sexual Artefacts,” Negotiating Sexual Idioms: Image, Text, Performance, ed. Marie-Luise Kohlke and Louisa Orza, Rodopi (2008).

Maya von Ziegesar holds a B.A. in philosophy and fine art from Princeton University. In the Fall of 2021, she’ll begin a PhD in feminist philosophy and philosophy of race at the CUNY Graduate Center, New York. From March until May 2021, she completed an internship at the Naomi Wilzig Art Collection project at the Research Center for the Cultural History of Sexuality at Humboldt University, Berlin.